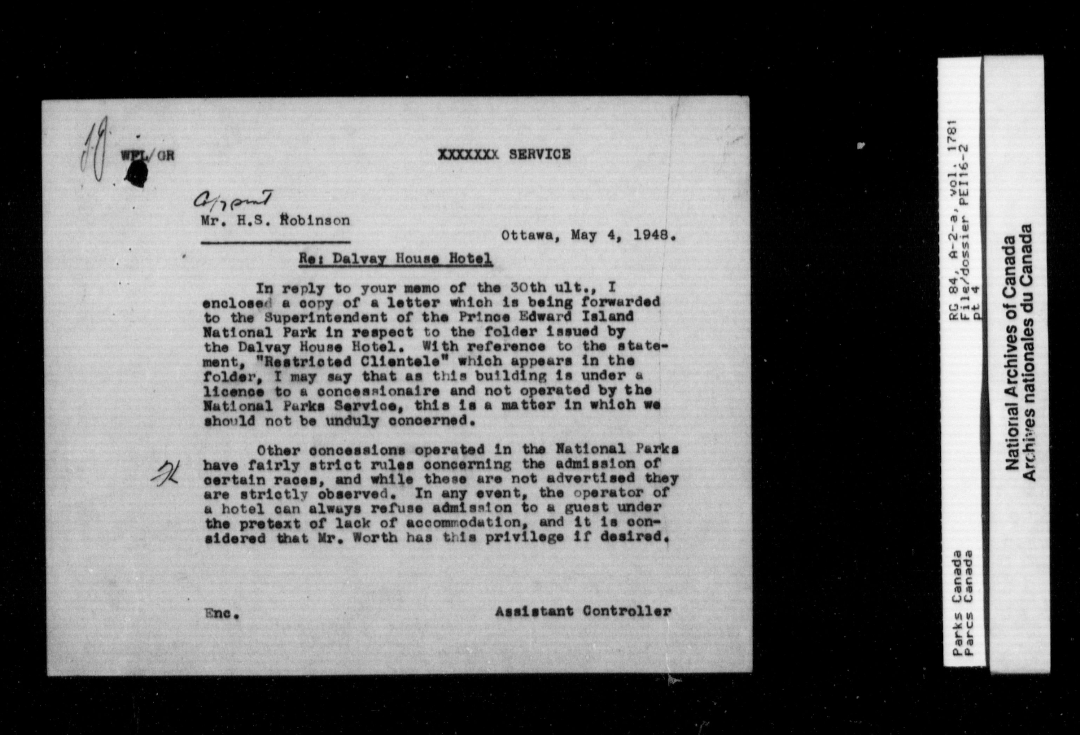

Lessons from Parks Canada's History Inform New Paths through the National Urban Parks Program

What is the National Urban Parks (NUP) Program?

Parks Canada is a Canadian federal agency with the mandate to “protect and present” nationally significant areas of land, and to preserve their ecological and cultural integrity for present and future generations to discover and enjoy. The 2002 Parks Canada Charter provides a base for the agency's current expansion and reimagination. In step with prioritizing inclusion as a core value, urban access to national parks has recently come into focus. In 2021, the Government of Canada committed $130 million to establish a network of up to six new national urban parks by 2025. These will complement the Rouge National Urban Park, which was opened in 2010 in the Greater Toronto Area.

The three core objectives or pillars of the new National Urban Parks (NUP) program are to: 1) conserve nature, 2) connect people with nature, and 3) advance reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

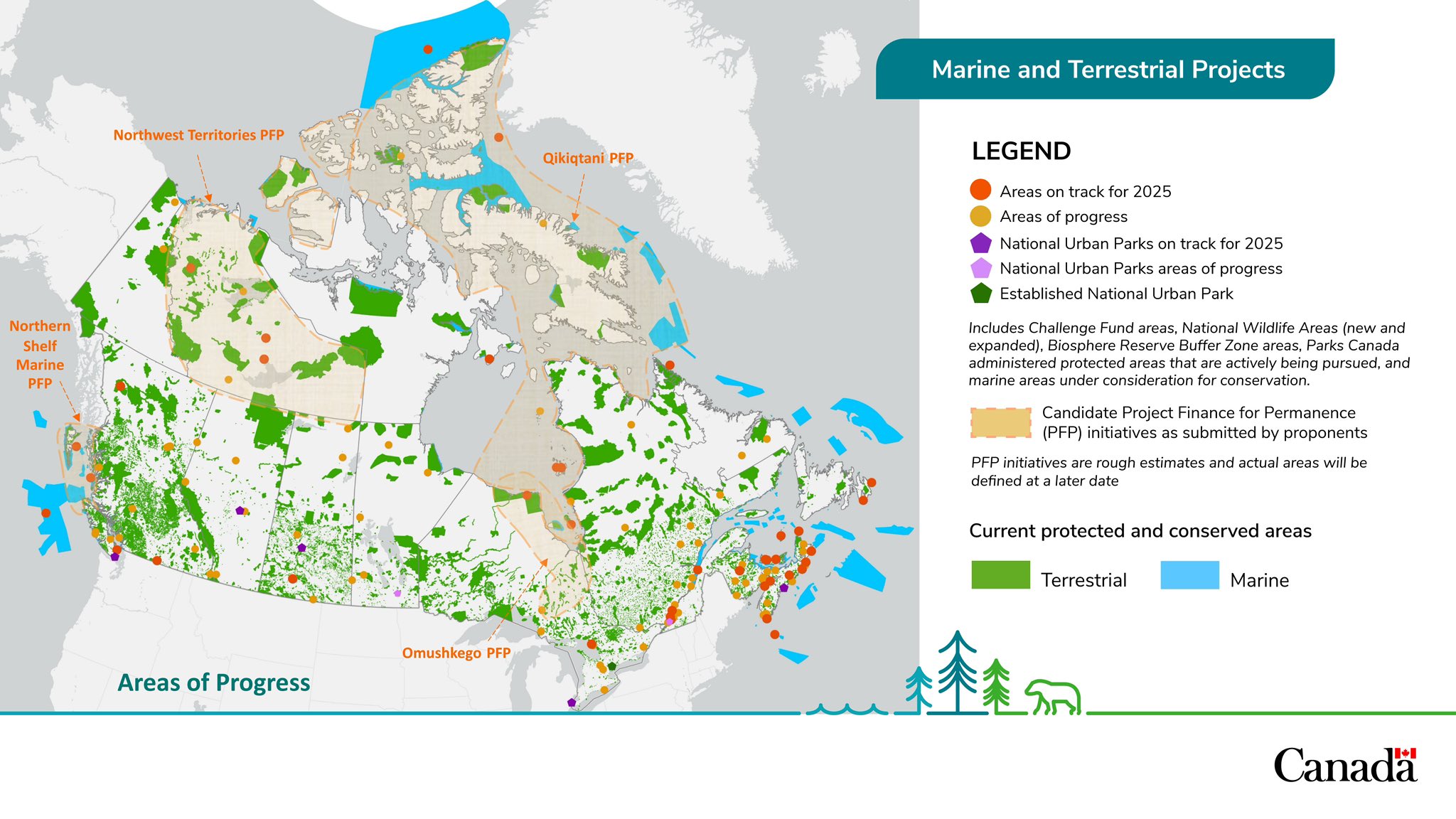

On the conserving nature pillar, the NUP program is part of the federal government's efforts to reach biodiversity targets in line with United Nations commitments. The government has set its benchmarks to conserve 25% of lands by 2025 and 30% by 2030. Canada's current and forthcoming protected lands are shown in the map below and can be viewed in greater detail using the interactive Canadian Protected and Conserved Areas Database (CPCAD) Open Map. The NUP program is vital to secure protected status for urban lands and protect the health of diverse organisms and habitats in densely populated areas.

Current and forthcoming protected lands in Canada. (Source: Government of Canada)

Pillars two and three of the NUP program centre reconciliation and inclusion through access to parks. As Parks Canada states:

Urban parks play an important role in improving quality of life, and creating more welcoming, accessible and inclusive communities. National urban parks will create spaces for all visitors to connect with nature, learn about natural and cultural heritage, and enjoy the benefits of spending time outside. They will seek to reduce barriers to ensure that more people can have meaningful experiences in urban green space.

Centring inclusion and reconciliation in the National Urban Park policy provides important opportunities for Parks Canada to continue to confront and remedy histories of dispossession of Indigenous and other communities, and other practices of discrimination and exclusion. This blog post explores some of this history, and its lessons for the NUP program.

The Dominion Parks Branch Legacy of Colonial Dispossession

Canada's national parks system was established under the Dominion Forest Reserves and Parks Act in 1911. The Dominion Parks Branch initially focused on five natural areas within western Canada along the Rocky Mountain range and used the forced labour of internment camp populations to build the park roadways and infrastructure.

Conservation has been a constant throughline in the history of the agency. However, settler conservationist ideals have not always recognized or respected traditional knowledge keepers. Iconic national park sites such as Banff, Jasper, and Yoho were cleared of the many Métis and First Nations communities that traversed the landscape for cultural, spiritual, and recreational use. A number of government programs and policies acted in concert with the federally designated park lands to constrain use by Indigenous people, including restrictive treaty agreements, forced attendance at residential schools, and the unofficial Pass System. The federal agenda of cultural genocide as described in the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada is woven into the country's history from its inception, and the dispossession of Indigenous people undertaken for the purposes of creating national parks, in particular in Western Canada, can be seen through this lens.

However, the tools of state-sanctioned dispossession have taken different forms across the country depending on the framing of national interests and the population affected. On the east coast, French-speaking Acadians were expelled by British authorities under the banner of national security interests and their lands, including the lands on which Cape Breton Highlands National Park is now situated, were given to British Loyalists. In New Brunswick, the formation of the Kouchibouguac National Park saw the federal agency and provincial government come to the agreement that Parks Canada would offer payment to vacate lands and the province would manage the expropriation and resettlement of those inhabitants. The drawn-out and fraught park planning process saw many Acadians removed through physical, legal, and financially oppressive tactics.

Up until the 1960s when environmental concerns and overdevelopment began to garner more public attention, National Parks were primarily designed with the objective of tourism, and more specifically auto-tourism for visitors “of suitable class” who had access to automobiles before they became more widely affordable. The Town of Banff in Banff National Park marketed the mountains as pristine and unoccupied while paradoxically co-opting images and caricatures of Indigenous groups for profit. Indigenous constitutional and sovereign rights to hunting and ceremony, such as the Kainai Nation's Sun Dance ceremony were forbidden and overpoliced. International tourism was encouraged selectively while racialized Black and Chinese visitors were intentionally made unwelcome (Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King were discouraged from visiting a hotel in New Brunswick's Fundy National Park in 1960).

A Local Example: Point Pelee National Park

Ojibway Nature Centre. Photo by Bernie Sistek on Unsplash.

Point Pelee National Park is the only existing National Park in the Windsor-Essex region. Just 63 km from the proposed National Urban Park site in Windsor, Point Pelee's story also includes histories of displacement and unequal access based on colonial practice.

The Alexander McKee treaty negotiation of 1790 gave the Crown title to the land on which Point Pelee sits. Many Indigenous residents were not represented by their leadership in this treaty negotiation. After the people of Point Pelee (now known as Caldwell First Nation) fought alongside British Captain Caldwell in the war of 1812, he promised to return the land. However, Captain Caldwell failed to convince political authorities to follow through on this promise. Point Pelee National Park was established on this land in 1918.

The designation of this land as a national park gained political support through the efforts of wealthy White groups such as the Essex County Game Protective Association and the Essex County Wild Life Association (ECWLA). These groups lobbied to protect their access to the “gentlemanly” sport of duck hunting. In the same breath, these groups admonished the group of generations-long French-descended residents of Point Pelee as “enemies of wildlife” (page 303). The secretary of the ECWLA, using class and race-based arguments, reasoned it would be unwise “to deprive the sportsmen of Ontario in favour of negroes and other gunners of countries to which our birds migrate.” The first Parks Commissioner, James Harkin, initially endorsed the continued duck hunting despite warnings from ornithologists to protect the marsh as an important migratory haven.

Point Pelee National Park is an important local case study shedding light on the historic dispossession of Indigenous and racialized communities, and people of lower socio-economic status, in the creation of National Parks. It further illustrates how marginalization in decisions of park use and governance has often been multi-layered and has affected multiple communities. It also shows how in park planning, some local voices have sometimes carried the day to the exclusion of others.

Reckoning with history

American coot. Photo by Lia Maaskant on Unsplash.

By its actions, Parks Canada has signalled a growing willingness to grapple with difficult Canadian histories, including those in which the agency itself was implicated. National Historic Site designation for Africville, NS recognizes the destruction of that community by governmental “urban renewal” policies. A “Memories of our Communities” display in Kouchibougouac National Park in New Brunswick tells the story of the Acadian dispossession for the purposes of creating the park.

Parks Canada has grown to encompass 10 national park reserves, referring to lands which are subject to one or more First Nation, Métis, or Inuit land claims, in addition to its 37 national parks. In its 2021-2022 report, the agency stated that their participation in Indigenous rights-based negotiations had approximately doubled since 2015. At the time of writing, the agency was participating at 66 negotiating tables and came close to its targets for the number of heritage places managed cooperatively with Indigenous peoples.

The agency has shifted to approach establishing new parks with less rigidity and more sensitivity to the cultural significance of land and water. The key to this new approach is partnership. For example, in 2019, Parks Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories reached agreements with four First Nations to establish protections for land known as Thaidene Nëné. Portions of the Thaidene Nëné Indigenous Protected Area have been designated a National Park Reserve, a Territorial Protected Area, and a Wildlife Conservation Area.

Today, Banff National Park has an Indigenous advisory circle to help foster relationships between various communities and Parks Canada. There now exists a system for facilitating park access for cultural use to nations with longstanding ties to the land.

However, while there are now indications of increased openness and trust from Parks Canada's side of the relationship - potentially providing Indigenous communities a better opportunity for dialogue - most of the power and control is still entrusted to colonial structures.

Opportunities through the National Urban Parks Program

Viewing Parks Canada's new NUP program through the lens of the agency's history provides an opportunity to recognize the lasting impacts of displacement and marginalization. It is a reminder to all involved of the proactive need to guard against recreating harmful processes. The establishment of the NUP program presents unique challenges and opportunities when compared to Parks Canada's existing portfolio because of the surrounding urban development, potential for co-management of infrastructure, and large local populations. The NUP program is an important part of Parks Canada's work to advance reconciliation and ensure more equitable access to national parks. Diverse community partnerships and Indigenous leadership will be necessary features of achieving this goal, along with comprehensive storytelling about the histories of the lands, how they have been used, and by whom.

Parks Canada's 2-year, $1.2 million contribution agreement for the University of Windsor National Urban Park Hub (UW-NUPH) is part of this commitment to support community-up approaches for advancing the NUP program's three pillars.

We acknowledge with gratitude the land, air, water, fire and all the beings of creation that sustain us. We honour the longstanding relations of many First Peoples to this place since time immemorial (including the Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee, Lunaapee, and Huron/Wendat Peoples). We acknowledge colonial harms. We commit to renewed and respectful relations to people, nature and this place.

® 2024 University of Windsor