Connecting Urban Windsorites to Nature Through Active Transportation

The provision of safe, efficient, and environmentally sustainable options for transportation connecting people with Nature is a challenge for urban communities, including Windsor.

Planning for the proposed National Urban Park (NUP) in Windsor must consider forms of transportation residents can use to access the NUP, developed through an equity lens. Active transportation is key in removing barriers to accessing parks in the NUP site.

This post explores the significance of active transportation infrastructure that could make the proposed NUP and other greenspace in Windsor accessible for more people, in line with NUPH's priority of “connecting Canadians to nature,” which “seek[s] to reduce barriers to ensure that more people can have meaningful experiences in urban green space.” Increasing active transportation is considered in the context of Windsor planning policy.

Figure 1: View of the Ojibway lands for the Windsor National Urban Park (Credit: University of Windsor)

Active Transportation in Windsor

The City of Windsor's most recent Active Transportation Master Plan (ATMP) defines active transportation as: “any active trip you make to get yourself, or others, from one place to another” which covers “any form of human powered transportation.” The most common forms of active transportation are walking and cycling. While active transportation is traditionally narrowed to include only “non-motorized” forms of transportation, walking or cycling may be integrated with other shared forms of motorized transportation, such as public transit. Some consider “multi-modal trips”, such as walking to a bus stop and taking a bus, to be a form of active transportation.

In a Fall of 2021 Transit & Mobility Survey conducted by the advocacy group Active Transit Windsor-Essex (ATWE), 57% of resident respondents strongly disagreed that it is easy to live in Windsor-Essex without a car, highlighting the need to improve active transportation options across the county.

Cities across Canada have begun taking more aggressive measures to support safe, active transportation options for commuting and recreational cycling. For example, Québec City recently announced that it will construct 150 km of cycling corridors that will connect most of its 35 neighbourhoods to places of work, schools, and libraries. Québec City's aim is to create a network of cycling pathways that give residents an alternative to using their cars, while simultaneously improving the economy and environment.

Gearing urban spaces toward greater usage of active transportation has positive impacts on municipal economies, the mental and physical health of residents, and the environment—including air quality amelioration and traffic reduction.

Active Transportation Infrastructure in Windsor is Insufficient for Equitable Access to the NUP

Use of multi-modal forms of transportation in Windsor remains low at 10% (2016). While this figure only includes commutes to/from school or work, not recreational multi-modal transportation, this research suggests that active transportation is not seen as a viable transportation option for most, for travel within Windsor. The relatively limited amount of safe active transportation infrastructure in Windsor is likely a factor.

Pedestrian infrastructure is limited

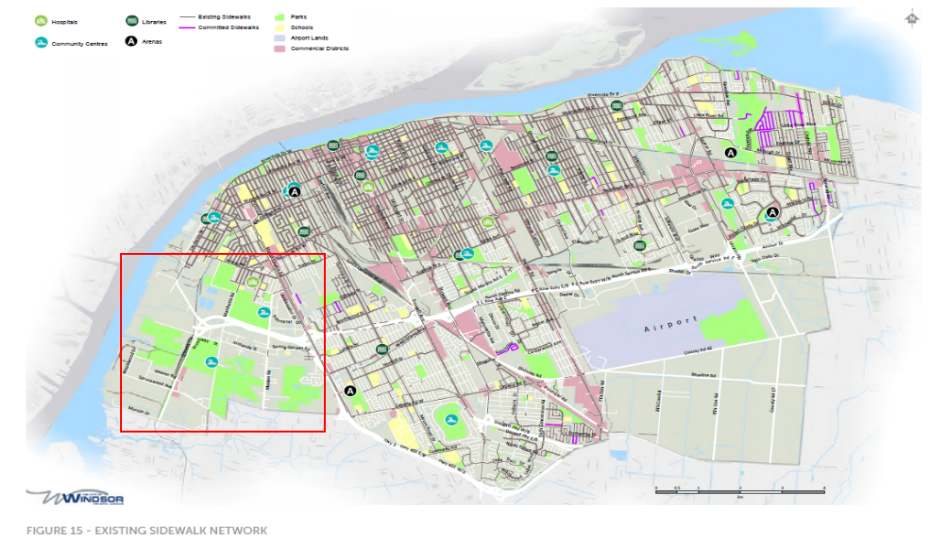

Approximately 62 km of arterial and collector roads in Windsor are constructed with a sidewalk on only one side, and 78 km with no sidewalk at all. Data from ATWE's Transit & Mobility Survey suggests that 27% of resident respondents find it “very difficult” to get to their destinations by walking. The lack of pedestrian infrastructure is pronounced around the NUP. Figure 2 illustrates the lack of existing sidewalks in and around the vicinity of the proposed NUP site. Public feedback from the NUP pre-feasibility phase indicates that accessing the park is challenging for residents without vehicles due to dangerous road conditions. The lack of sidewalks around the NUP may deter residents from accessing the park by foot, as respondents indicated interest in creating crosswalks and pedestrian connections.

Figure 2: Map of existing sidewalk networks in Windsor (Source: City of Windsor, “Active Transportation Master Plan: Final Report” (May 2019) at 26)

Cycling infrastructure is limited

While the City of Windsor is commonly referred to as the “Automotive Capital of Canada” for its deep historical roots in the automotive industry, the City's cycling history has been “significant and unbroken”. Yet many years of municipal underinvestment in cycling infrastructure weaken that legacy. Windsor currently has a mixture of both on-street and off-street cycling infrastructure, including 50 km of bicycle lanes and paved shoulders, 30 km of cycling ways or “shared use lanes” with signage, and approximately 130 km of “multi-use pathways. Data from the ATWE shows that Windsor-Essex still needs to improve cycling infrastructure given 24% of resident respondents indicate they find it “very difficult” to reach destinations by cycling.

Figure 3 shows the City's existing cycling network and infrastructure. From this figure we can see that there are limited bike lanes in the downtown core that connect residents to the “Windsor Loop”—a 42.5 km loop of cycling ways around the City. The Windsor Loop allows cyclists access to the NUP by connecting them to the Trans Canada Trail, through Sandwich, and around Malden Park, the Spring Garden Natural Area, and the Oakwood Natural Area. Cyclists and pedestrians can access Broadway Avenue, which is approximately 500–600 meters short of the entrance to Ojibway Park, leaving people to cycle or walk on the unpaved shoulder to access the NUP.

In 2021, the City of Windsor approved a $1-million temporary cycling infrastructure project that would have created protected cycling lanes along a segment of University Avenue, from Huron Church to Crawford Avenue, but in 2023 reversed its decision, instead opting to wait for the permanent project. It is reported that this project could take over ten years for the City to complete. Until this key connector is complete, safe cycling from the downtown core to the NUP will be an elusive goal.

Figure 3: Map of existing cycling networks in Windsor (Source: City of Windsor, “Active Transportation Master Plan: Final Report” (May 2019) at 27)

Public transit infrastructure is limited

Data from the ATWE survey suggest that trip length, unreliability, and infrequency of bus service have all been cited as deterrents to Windsorites relying on public transit. Thirty percent of Essex County participants stated that they stopped using public transit in the region due to failure of buses to arrive on schedule. Furthermore, 22% of Windsor-Essex residents stated it is “very difficult” to reach their destination by taking public transit. Residents may be deterred from using it to visit the NUP for similar reasons related to trip length, reliability, or frequency of service. For instance, residents who live in the downtown core at present would currently need to take multiple buses and could spend up to 1.5 hours travelling one way to reach the NUP candidate site. These limitations raise important concerns about the feasibility of residents' ability to access the proposed NUP in the absence of new and significant investments in active and public transportation infrastructure.

New Gordie Howe International Bridge Crossing

The Gordie Howe International Bridge project features a dedicated multi-use path that will facilitate toll-free pedestrian and cyclist traffic across the Windsor-Detroit border. This one-lane pathway is designed to support two-way movement and is 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) in length and 3.6 meters (11.8 feet) wide.

This path will no doubt increase access to the proposed NUP from the United States and has been touted as being able to connect Ojibway NUP with Rouge Park, Michigan's largest urban park. Public consultations were held in early 2024 to gather input on operational policies related to access, safety, and user experience. The finalized Terms of Use for the path will be announced prior to the bridge's opening in 2025. The multi-use path represents a significant step toward fostering sustainable and inclusive cross-border transportation.

Equitable NUP Access and Active Transportation

In Windsor, the lack of availability of reliable and safe active and public transportation options is an equity issue. Data from the 2021 census ranks Windsor as having the fifth highest income inequality among major cities in Canada, with downtown and Windsor's west end having some of the highest levels of child poverty in the province. Census data also reported that 11.3% of households in Windsor are considered low-income. As of 2019, 75% of Windsor residents earn less than $50,000 per year. The average annual cost of operating and maintaining a vehicle in Canada in 2024 is over $15,000—out of reach for many low-income residents. For a large sector of Windsor residents, reliance on walking, cycling, and taking public transit is their only method of transportation.

The proposed NUP site is located in an area that currently lacks safe and reliable active transportation infrastructure and is also remote from some of the City's most densely populated areas, such as the downtown core. Therefore, residents who own vehicles stand to have easier access to the NUP than residents relying on active transportation. Indeed, pre-feasibility phase public engagement data suggest that 50% of resident respondents plan to use only their vehicles to visit the NUP.

To accomplish the NUP priority of connecting people to nature, there must be sufficient planning and adequate investments in active transportation infrastructure, supported by meaningful engagement with residents.

In determining the need for more transportation options, broader questions arise: What does access to Nature or connection to Nature truly entail? How does the conversion of Ojibway Park lead more people to access Nature? Should we be looking at other areas across the City where people access and connect with Nature and look to increase the percentage of greenspace overall across the wider community?

Access to the NUP and other naturalized spaces in the city must be equitable, which requires that active and public transportation options must be at least as viable as vehicle-based access. Further, regardless of which naturalized spaces Windsorites are trying to reach, improved active and public transportation infrastructure and services will lead to more equitable access for all.

The C4C National Urban Park Hub team includes Anneke Smit, Rino Bortolin, Dorian Moore, Terra Duchene, Hannah Ruuth, Safa Youness, Ali Mokdad and Jana Jandal Alrifai. Special thanks to Terra Duchene for support on this post. Tamara Belley is a 2024 Windsor Law graduate and worked with the C4C NUPH team from 2022 to 2024. She is currently articling with a full-service law firm in Ottawa.

We acknowledge with gratitude the land, air, water, fire and all the beings of creation that sustain us. We honour the longstanding relations of many First Peoples to this place since time immemorial (including the Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee, Lunaapee, and Huron/Wendat Peoples). We acknowledge colonial harms. We commit to renewed and respectful relations to people, nature and this place.

® 2024 University of Windsor