Urban Design at Ojibway Park: Access, Connectivity, and Equity

The proposed designation of Ojibway Park as a National Urban Park is a transformative opportunity for Windsor's future. As a vital ecological asset, Ojibway Park can link Windsor's natural and urban spaces. Realizing this vision requires strategic urban design to overcome barriers and strengthen connections between the park, Sandwich Town, and key infrastructure like the Gordie Howe Bridge. Prioritizing pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, green corridors, and multimodal transport will create an inclusive, sustainable space that honors Windsor's cultural heritage. This integration will enhance Ojibway Park's access and set a national standard for equitable urban development.

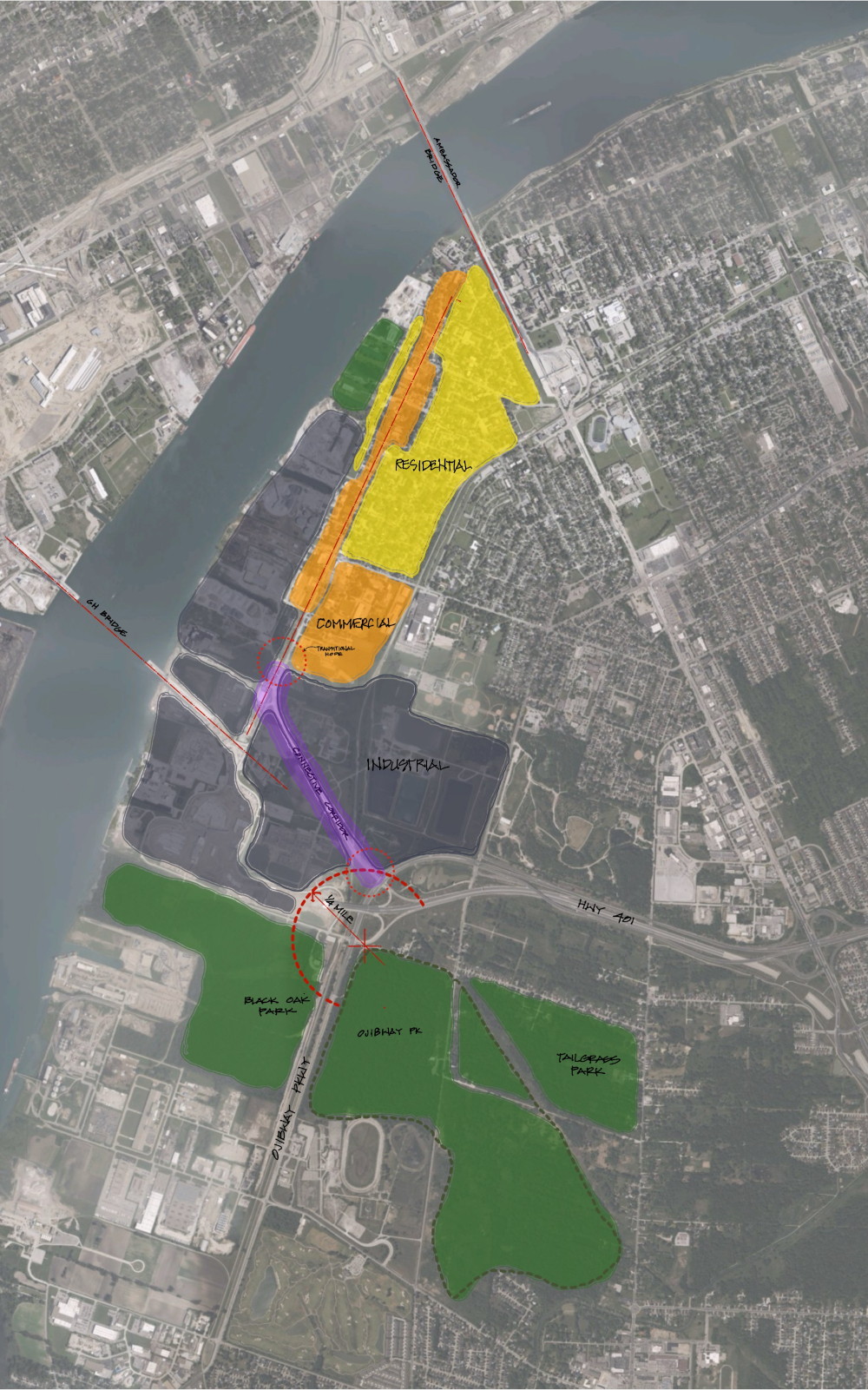

Concept sketch of Ojibway Park area showing critical areas of connectivity (highlighted in purple)

Objectives of Canada's National Urban Parks

The Federal Government's National Urban Parks Policy aims to expand urban parks to conserve nature, connect people with nature, and advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. These goals support the equitable integration of Ojibway Park and Indigenous communities—true stewards of these lands—into Windsor's broader community.

Equity is achieved by recognizing and enhancing existing assets, creating value in the process. This is especially true for Ojibway Park, a well-known but often underappreciated city asset. Urban design can help highlight and strengthen this value.

The Role of Urban Design at Ojibway Park

Urban design shapes the physical features of cities to create functional, sustainable, and attractive environments. It involves the arrangement of buildings, public spaces, transport systems, and amenities to improve urban life. For Windsor, improving connections between Ojibway Park, Sandwich Town, Highway 401, and the Gordie Howe Bridge presents a significant opportunity. Strategic interventions—such as reconfigured intersections, expanded sidewalks, designated cycle paths, improved transit stops, transitional public spaces, and new development sites—can strengthen these connections, benefiting Sandwich Town, the city, and park visitors.

Connectivity is fundamental to urban design. Ojibway Park's main challenge is connecting to its surroundings. Research shows most people are willing to walk about a quarter-mile before opting to drive. With the Ojibway Nature Centre about three miles from Sandwich Town, the walking experience must be more than functional—it must be safe, useful, comfortable, and interesting, as highlighted by walkability expert Jeff Speck.

The five-minute walking distance (pedestrian shed) is a standard for how far people are willing to walk. This distance varies based on destination type and walk quality. It extends for destinations like transit stops but shrinks when safety is a concern, particularly for children accessing parks (Wolch, 2002).

A study in Austin, Texas, compared walking habits across neighborhoods with similar density but different layouts. Residents in traditional, less car-dominated areas walked farther than those in auto-oriented neighborhoods (Shriver, 1997). This underscores the need for safe, urban, and comfortable pedestrian and cycling infrastructure linking Ojibway Park to Windsor.

Ojibway Park's Context

Windsor's unique mix of amenities includes the Detroit River, industrial heritage, and cultural diversity. Sandwich Town, one of Windsor's oldest neighborhoods, played a significant role in the Underground Railroad, offering potential for a cultural corridor connecting to Ojibway Park. The park's diverse ecosystems offer a natural escape from urban development. The Gordie Howe Bridge, under construction, will improve regional connectivity with multimodal access to the U.S.

Surrounding Ojibway Park are industrial lands, highways, and international crossings. These can be seen as barriers or as opportunities to improve public infrastructure and redefine accessibility. Emphasizing walkable and bikeable connections is crucial for creating equitable access.

Barriers to Connectivity

Despite their proximity, Ojibway Park, Sandwich Town, and the Gordie Howe Bridge are poorly connected, even for vehicles. This lack of connection poses challenges—limited pedestrian access, fragmented infrastructure—but also opportunities for inclusive, green, and equitable design solutions. Addressing these barriers can create an interconnected urban network that fosters social interaction, environmental stewardship, and cultural inclusion.

Key barriers include:

-

Highway 401 Access: Difficult park access due to expressway termination and highway access demands strategic urban design. Traffic calming measures, road diets, and pedestrian infrastructure are essential.

-

Industrial Lands: Industrial zones hinder pedestrian and cyclist access from Sandwich Town. Infrastructure improvements must enhance the walking and cycling experience despite these industrial functions.

-

Bridge Traffic: The Gordie Howe Bridge will increase truck traffic, making the area less welcoming for pedestrians and cyclists. While pedestrian and cycling facilities are planned, connecting the park to the bridge lacks priority. Safe pathways beyond the bridge plaza are critical for fully integrating Ojibway Park into Windsor.

Urban Park Connectivity Precedents

Windsor can learn from global examples of successful park integration:

-

New York's Central Park: Central Park bridges urban and natural spaces through pedestrian sidewalks, promenades, and parkway drives.

-

Toronto Ravines: Toronto's ravines offer a natural amenity seamlessly woven into the urban landscape, with numerous access points and permeable boundaries.

-

Boston's Big Dig & Dallas' Klyde Warren Park: These projects transformed highway divides into cohesive public spaces. Windsor's Herb Gray Parkway similarly caps highways with parkland, linking to the proposed Ojibway National Urban Park from the eastern side.

Ojibway Park's peri-urban setting presents a chance to adapt lessons from these models to Windsor's context.

Conclusion

Strengthening connections between Ojibway Park, Sandwich Town, and the Gordie Howe Bridge offers Windsor a chance to enhance urban connectivity, drive sustainable development, and celebrate cultural heritage. Prioritizing pedestrian-friendly design, green corridors, cultural preservation, multimodal access, and community engagement can create a vibrant, inclusive urban landscape.

By emphasizing pedestrian and cyclist safety, Windsor can reduce vehicle reliance and traffic congestion. Through innovation, collaboration, and sustainability, Windsor can become a model for modern urban design and inspire other cities to prioritize people, nature, and prosperity. Thoughtful design of Ojibway National Urban Park can also guide other National Urban Park projects across Canada.

References

Shriver, Katherine, Influence of Environmental Design on Pedestrian Travel Behavior in Four Austin Neighborhoods, Transportation Research Record, 1997.

Wolch, Wilson, J., and Feherenbach, J., Parks and Park Funding in Los Angeles: An Equity Mapping Analysis., The University of Southern California Sustainable Cities Program, 2002.

We acknowledge with gratitude the land, air, water, fire and all the beings of creation that sustain us. We honour the longstanding relations of many First Peoples to this place since time immemorial (including the Anishnaabe, Haudenosaunee, Lunaapee, and Huron/Wendat Peoples). We acknowledge colonial harms. We commit to renewed and respectful relations to people, nature and this place.

® 2024 University of Windsor